Luisa Rebull | Photo Courtesy of Luisa Rebull/ Caltech

Who: Luisa Rebull: Astronomer

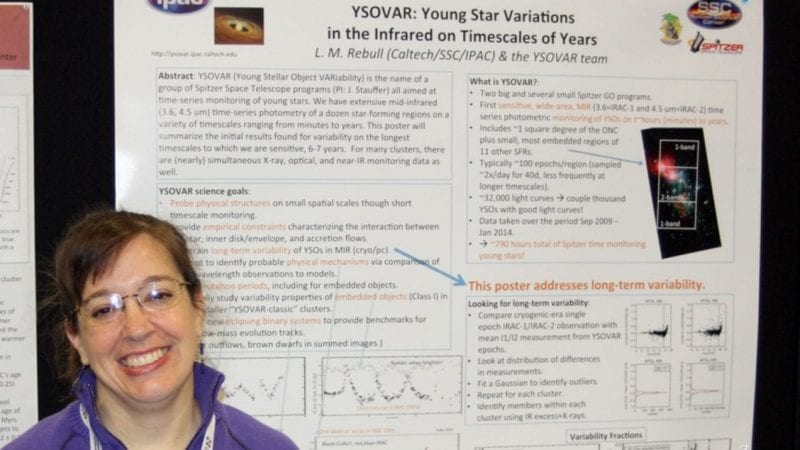

What & How: Associate Research Scientist. "I do scientific research. I study how baby stars form, and how the rotation rate of stars changes with time. This has bearing on how/when/where stars form planets and ultimately life. As part of being a scientist, I write proposals; plan observations and collect data; analyze and interpret the data, draw conclusions; collaborate with colleagues; write journal articles; travel to conferences to present my results and serve on review and/or advisory committees. My job has a lot of travel and a lot of computer programming.

I also support one of NASA's archives called IRSA, the NASA/IPAC Infrared Science Archive. This is the home of NASA's infrared data, as well as lots of other astronomical data. I help create and maintain the archives and help astronomers (and educators) use the archives. We have to make all of the data easily accessible and usable by the worldwide astronomical community. We develop tools that help astronomers make discoveries.

I also help high school science teachers learn how real research is conducted. I run a program, the NASA/IPAC Teacher Archive Research Program (NITARP), that partners small groups of educators with a research astronomer for a year-long astronomy research project. We help the teachers learn how science works, so that they can turn around and share that knowledge with their students."

When: "Research and work for NASA, like parenthood, are "anomic" jobs. Anomie is a term I learned from sociologists/psychologists invited to speak at conferences specifically convened to discuss women and underrepresented communities in astronomy and science in general. In this context, anomic jobs are those which have no boundaries -- you can literally work every waking minute and never be done. Having more than one of those jobs is tough, let alone three! I try to limit my work hours to a reasonable number and try to be emotionally present when home. That doesn't always mean 40 hours at work exactly. Boundaries are fluid and continually adjusting. Some weeks my family needs more time. Some weeks the archives need more time. Some weeks the science needs more time."

Where: "I work at Caltech (the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA) at a place called IPAC. IPAC supports many long-wavelength NASA astrophysics missions and surveys, some still operating and some no longer operating but with rich data in which there are still discoveries to be made."

Why: "I have always seen myself in this kind of a job -- it is literally my dream job. I am doing astronomy research and supporting NASA missions. I have always wanted to be an astronomer, ever since I was very little. I grew up in the Washington, D.C. area, where my favorite museum, no contest, was the National Air and Space Museum. As a kid, I was a "NASA junkie," collecting NASA lithographs, which was how NASA made "pretty pictures" available to the public before the web. I was born after Apollo 11, but the sheer coolness of NASA things was indescribable, and the images from Voyager mission hit me at just the right time to really entrance me."

Image of North America Nebula | Photo Courtesy of Luisa Rebull

Best part about the work: "Working with lots of really dedicated, smart people towards a common goal."

Biggest challenge of the work: "Financial uncertainty. Government shutdowns. Moving of the general public away from science and the funding thereof. A little bit more stability would be nice. NASA does amazing things with less than one half of one percent of the Federal budget, and that includes not just astrophysics but also planetary exploration, Earth observations, and crewed missions; the first "A" in NASA is aeronautics (planes), and NASA does a lot of work there, too.

Being a scientist, where facts matter, in the context of the current political climate: "There's a series of maps from worldmapper.org. The first map shows Earth like you think of when you think of a map of the Earth, with the size of the countries scaled by their area.

The next map has the countries' size scaled by their scientific output. The U.S is huge, Europe is enormous, South America shrinks to almost nothing, Africa shrinks even more, the East Asian countries like India and China are there but not enormous.

The next map is scaled by *rate of change* of scientific output. Europe is about the same size. The U.S. shrinks. South America is bigger as many of those countries invest in science. India becomes enormous, China huge, as are various Middle East countries that are starting to invest in science. Africa is still a tragedy. This map should concern everyone who's concerned about the U.S. maintaining scientific leadership in the world. The fact that other countries are pouring money into scientific research and that the U.S. is stepping back should worry every U.S. citizen. Less investment in science means we cede leadership. Investment in science drives economic growth; this has been shown again and again."

Sharing astronomy: "I enjoy sharing what I do with the general public. I feel strongly that since taxpayers help pay for my salary, they deserve to find out what I do in terms that they can understand. I've done lots of different education and public outreach things, but a recurrent theme over the last, gosh, 25 years is working with teachers. I've been involved in a few major efforts to bring more technology and authentic science into the high school classroom. As noted above, the NASA/IPAC Teacher Archive Research Program (NITARP) is the program I run now. It is so much fun to teach people who really want to learn, and I learn a lot from them too. And through them, I indirectly reach the students they have this year, and next year, and through the rest of their careers. It's hard to beat that leverage."

Gender gap: "I think it's better now then when I was a kid. There was a recent study where kids were asked to draw a scientist. A much larger fraction of the scientists that they drew were women, more than in earlier similar studies. That's a really good sign. The problem is that there's also been some recent research pointing out that girls are enrolled in math and science classes at a much higher rate than they ever have been before -- but then they don't stay in. So now the question is, OK, we got them interested but why are they leaving? I suspect it has something to do with culture. I'm not sure exactly at what point that happens, whether they make it to college and don't persist through college, or they don't last long in the workforce. There are lots of anecdotal stories of women lost to STEM careers at both these stages. I don't know enough to say whether it's the college culture or the workforce culture that is the bigger problem, or how to fix either. I'm sure that both of those are intertwined with each other."

Stereotypes matter: "As a girl interested in science and technology, sometimes I felt a little left out. In kindergarten, for the after-Christmas show-and-tell, I was in tears because I was the only little girl who didn't bring in a doll -- I brought my motorized Lego set, which I hadn't put down since I got it. (I had received dolls, but they were still in their plastic packaging!) Sometime in mid-elementary school, I learned astronomers needed math, and somehow (despite my parents' best efforts), I decided that of course girls can't do math. It took me until college to get over that."

She persisted: "My parents were the ones who were really supporting me [in science and math.] By the time I was in middle school, when I was in 7th grade, I was the only girl in the science class and was horribly bullied. By the time I was in high school, I had a little bit more, for lack of a better term, "hard-headedness." And certainly by college, I had the attitude of, 'Yup I'm here, and I'm not going to leave until I'm ready to leave.' So, it helps to be a little stubborn and hard-headed."

Astronomy prep: "I went to the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, VA because it was good in a lot of different things. I figured if I didn't like physics, I'd major in chemistry or maybe even history. Much to my surprise, I did like physics, and I was pretty good at it. (I ended up taking a lot of Colonial American history too.) I went to grad school in astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Chicago. In college, math was a tool to be gotten through as soon as possible so you could get to the physics, and in graduate school, physics was a tool to be gotten through as soon as possible so you could get to the astrophysics! That doesn't mean that I find these things easy, just that they are something to be gotten through as soon as possible-- sort of like Brussel sprouts!"

All in the family: "My husband is also an astronomer -- we met in grad school at the University of Chicago. We have a son who was born in 2008. Somehow, our son is an athletic morning person; he's just made his second degree black belt in Taekwondo. As any working mother does, I am continually trying to figure out how to be a supermom."

Hope for the work in future: "That I still get paid to do all these wonderful things until I choose to retire!"

Luisa's Astronomy Visuals:

http://web.ipac.caltech.edu/staff/rebull/starform/

Luisa Rebull | Photo Courtesy of Luisa Rebull/ Caltech